Caucasian Internment Camps in the Philippines During WWII

During World War II, the United States forced 120,000 Japanese Americans into internment camps. The action represented one of the darker moments in American history. At the same time, the Japanese were taking similar action in the Philippines. This is the story of Caucasian internment during the Second World War.

The Japanese Take Over the Philippines

At the outset of World War II, the Philippines were a commonwealth of the United States. On the same day that the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, they also began an operation in Luzon. Within three weeks, the Japanese Army was able to take over the Philippines. The 20,000 American and 80,000 Filippino troops who had been on the ground departed to the Bataan Peninsula. Any remaining American or British citizens were ordered to stay in their homes until they could be registered.

Internment Begins

After Caucasians were rounded up in Manilla, they were transferred to the University of Santo Tomas. In addition, there were also around 70 African-Americans and Filipino spouses or internees. There didn’t seem to be much of a plan, and the internees mainly were left to fend for themselves. The only exceptions were a 7:30 PM roll call each night and the use of room monitors. The background of the captives varied wildly from business executives to retired soldiers to prostitutes. Some came with pockets full of cash, and some were entirely broke.

The Japanese did little to provide food or services, so the captives were forced to set up their own society of sorts. A man named Earl Carroll oversaw an executive committee that made decisions for the camp. Ernest Stanley, a missionary who had lived in Japan, acted as an interpreter. The captives developed both a police force and a hospital that had several actual nurses and doctors. There was also a kitchen set up to provide morning and night meals for detainees that couldn’t afford food from the outside.

Issues with the camp

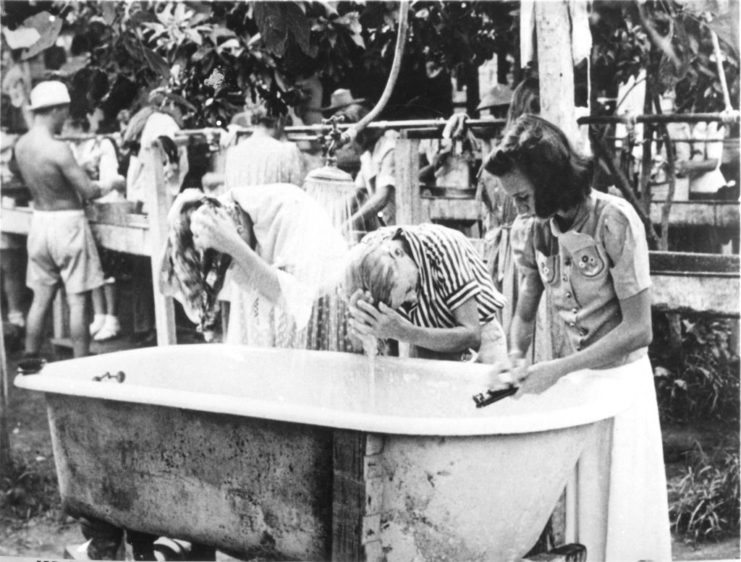

Despite the captive’s best attempts to set up services within the camp, there were some significant issues. The biggest problem was sanitation. 1200 men lived in the camp, and they had to share 13 toilets and 12 showers. Shelter during the heat of the day could also be hard to find. Again the wealthier captives were in luck here as they were able to build shanties out of bamboo and palm fronds.

The executive committee attempted to fix some of the sanitation issues by creating a health committee. The health committee, which was made up of 600 interned men, was tasked with building toilets and showers, disposing of the camp’s garbage, and controlling the flies, mosquitoes, and rats. For the first two years of the camp, the sanitation practices were successful as there were no significant disease outbreaks.

Things got much worse as the war went on

As the war turned for the American side, things got worse at the camps. Due to overcrowding, 800 men were transferred to a center called Los Banos. Eventually, the Los Banos campus, 37 miles away from Santo Tomas, would grow to hold over 2,000 captives. Those captives were rescued in a raid conducted by American soldiers and Filippino guerillas in February of 1945.

At Santo Tomas, supplies like food and soap began to run short. While there was a fund for destitute detainees, funds were running out. Things got worse in November of 1943 when a typhoon destroyed many of the camp’s food and supplies. A month later, the Red Cross delivered a 48-pound box of food and supplies for each internee. This would be the first and last rescue package from the Red Cross.

In February of 1944, the Japanese Army took over command of the camp from the civilian executive board. Captives could no longer buy supplies or food from outside sources. Food was now being rationed, and many internees became profoundly malnourished. Various diseases, mainly avoided thus far, began to run rampant through the camp, and death became a regular occurrence.

The captives are freed

After the Allied forces fought the Battle of Leyte in October of 1944, rumors began to swirl that they would soon be coming to liberate Santo Tomas. The American troops were making haste as they thought that the detainees might be killed by the Japanese. The Japanese in charge of the camp took 200 hostages before the arrival of the American troops. When the Americas reached the bases, negotiations were made, and the prisoners were freed.

The total number of prisoners liberated was 3,785, with 2,870 being American. They could not leave the Philippines immediately, as fighting was still rampant on the island. Evacuation began slowly. Some internees chose not to return to America, hoping to return to their pre-war lives in the Asian country. The majority of detainees received a combat ribbon for “contributing materially to the success of the Philippine campaign.” Earl Carroll, who oversaw the camps, was honored with the Medal of Freedom.

The post Caucasian Internment Camps in the Philippines During WWII appeared first on warhistoryonline.

Post a Comment

0 Comments