A B-52 Stratofortress Once Crashed in North Carolina, Dropping Two Nuclear Bombs

The Cold War was a time of uncertainty across the world, particularly in the United States, where the majority of the population feared a nuclear attack by the Soviet Union. The government had B-52 Stratofortress bombers, armed with nuclear bombs, in the air 24/7, to ensure their crews would survive such an attack and be able to retaliate.

The “Keep 19,” a B-52G-95-BW bomber with the 4241st Strategic Wing, was on one of these missions above the Atlantic Ocean when disaster struck, resulting in its two thermonuclear bombs falling to the ground.

Refueling disaster

In late January 1961, the Keep 19 was commanded by Major Walter S. Tulloch of the US Air Force and piloted by Captain Richard W. Hardin and 1st Lieutenant Adam C. Mullocks. The bomber and its crew of eight had embarked from Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in Goldsboro, North Carolina for a routine flight along the east coast. Aboard the plane were two Mark 39 thermonuclear bombs.

The Mark 39, produced between 1957 and 1959, was a two-stage, radiation-implosion thermonuclear bomb. Each weighed more than 6,200 pounds and had within them two nuclear cores. When detonated, they could release the energy of 3.8 million tons of TNT, resulting in a blast that would immediately kill everyone within a 17-mile radius.

According to the US government, “it was fully fused, meaning it could be detonated by contact with the ground as an air burst, or ‘lay down’ – a series of parachutes would slow the bomb and it would touch down on its target before detonating, allowing the bomber time to get clear of the blast zone.”

In order to detonate, seven steps had to occur: the arming wires needed to be pulled; the pulse generators, activated; the explosive actuators needed to be fired; the timers had to start; the barometric switches needed to be engaged; the low-voltage batteries, actuated; and the ARM/SAFE switch needed to be moved to “ARM.”

When the B-52 met up with its refueling plane, the pilot noticed the bomber’s right wing was leaking jet fuel, with 5,400 gallons lost within three minutes. As such, its crew was ordered to turn around and make an emergency landing.

Unfortunately, before this could occur, the ring wing broke off, followed by part of the bomber’s tail. Tulloch ordered his crew to eject, and the plane crashed nose-first into a tobacco field just outside Goldsboro. Three crew members were killed in the incident.

Bombs falling to the ground

As the B-52 was falling to the ground, its bomb bay opened. One of the Mark 39 bombs deployed its parachute and ended up stuck in a tree, with its nose just barely touching the ground. When a military crew examined it, it found the ARM/SAFE switch was still turned to “SAFE,” meaning there wasn’t a risk of it detonating.

The second bomb was a different story. It deployed its parachute and struck the ground, disappearing into the dirt of the tobacco field. It took a week for the crew to dig it out, a process which included pumping groundwater out of the site.

While the bomb hadn’t detonated, it had disintegrated upon impact, meaning the excavation included a search for missing parts. When the ARM/SAFE switch was found, the crew saw it had been turned to “ARMED,” causing them to question why it hadn’t exploded.

While the majority of the second Mark 39 was found, one key part wasn’t: the secondary core. A report on the incident suggested it had likely lodged itself between 100 and 200 feet below the ground. Unlike the first core, it contained primarily uranium-238, a non-weapons-grade material. It did, however, contain some uranium-235 – or HEU – which is the key ingredient in the development of atomic bombs.

If the second bomb had detonated, it’s estimated the blast would have been around 250 times more powerful than that of Little Boy, which devastated Hiroshima during the final stages of the Second World War. Its fallout would have been deposited across the northeast, as far north as New York City.

Files become declassified

At the time of the incident, the Pentagon claimed there was never a chance of the bombs detonating, as their arming mechanisms hadn’t been activated. A spokesperson with the Department of Defense also stated that the bomb that crashed into the field had been unarmed and thus wouldn’t have exploded.

In 2013, The Guardian published a declassified document about the incident. It stated that, in 1969, Parker F. Jones had found the bombs “were inadequate in their safety controls and that the final switch that prevented disaster could easily have been shorted by an electrical jolt, leading to a nuclear blast.”

Out of the four safety mechanisms built into the bomb, three had failed to operate correctly. As The Guardian wrote, “when the bomb hit the ground, a firing signal was sent to the nuclear core of the device, and it was only that final, highly vulnerable switch that averted calamity.”

Another declassified memo, this time from Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, stated that it was only “by the slightest margin of chance, literally the failure of two wires to cross, [that] a nuclear explosion was averted.”

What happened to the crash site?

According to reports, the field where the B-52 crashed is safe enough to farm. However, to ensure nothing is ever built on the site, the US military purchased a 400-foot easement.

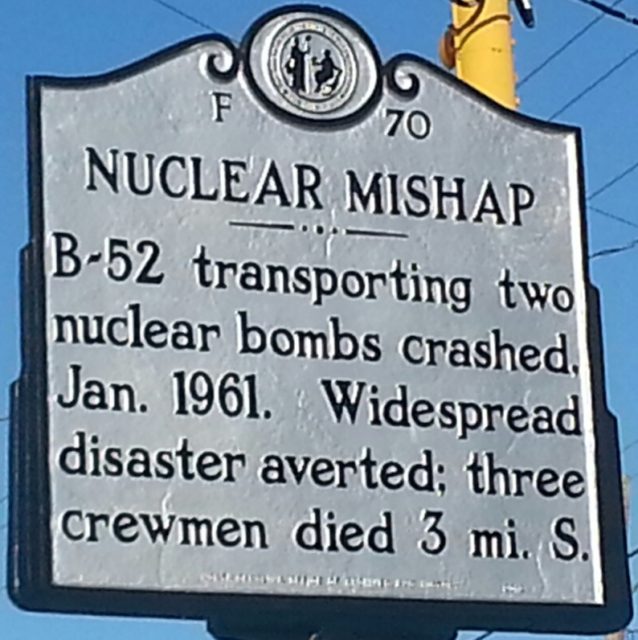

In July 2012, the state of North Carolina erected a road marker in the town of Eureka, just three miles north of the crash site, to commemorate the incident. It has since been dubbed a “Nuclear Mishap.”

The post A B-52 Stratofortress Once Crashed in North Carolina, Dropping Two Nuclear Bombs appeared first on warhistoryonline.

Post a Comment

0 Comments