There’s a receipt for the Hiroshima Nuclear Bomb

One of history’s most significant receipts ever signed still exists today. It was issued to mark the successful delivery and use of the Little Boy atomic bomb, which would be the first atomic bomb used in combat.

After billions of dollars and years of intensive research and development to produce a working atomic weapon, the atomic bomb “Little Boy” was shipped out to the Pacific. When it was handed over to the crews on Tinian, a receipt was signed. It is perhaps the most terrifying yet unique receipt ever created.

US atomic weapons program

In the late 1930s, European physicists sent a letter to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning him of the Nazi’s worrying atomic weapons research. At that point, the US had been conducting their own research into this matter, but they had been on a relatively small scale.

The intensity of this work increased after Roosevelt received the letter (known as the Einstein–Szilárd letter) and added information from intelligence services about German progress. In 1942, the US officially began the Manhattan Project, which turned the ongoing atomic research into a fully-fledged military program.

While it’s most famous for the development of the atomic bomb itself, the Manhattan Project encompassed enormous amounts of smaller projects all working on unique problems to create the bomb. In fact, almost all of the Manhattan Project’s resources went into the production of fissile material for the bombs. In total, the project cost just under $2 billion, an amount close to $30 billion today.

The project oversaw the development of two atomic bomb designs; the gun-type, which used uranium, and the implosion-type, which used plutonium. Plutonium was easier to collect, but the implosion bomb was much more complex and its feasibility was not trusted, so this type was the only one to be tested before use. In addition, the first completed gun-type bomb, called Little Boy, used all of the Manhattan Project’s uranium 235, so there would not be a test of this weapon.

The Trinity test on July 16 1945 was the first detonation of an atomic weapon and proved the implosion bomb worked. But on this same day, Little Boy left the US aboard the USS Indianapolis, headed for Tinian in the Pacific.

As this was the transfer of dangerous cargo, it required a paper trail.

One atomic bomb please, keep the change

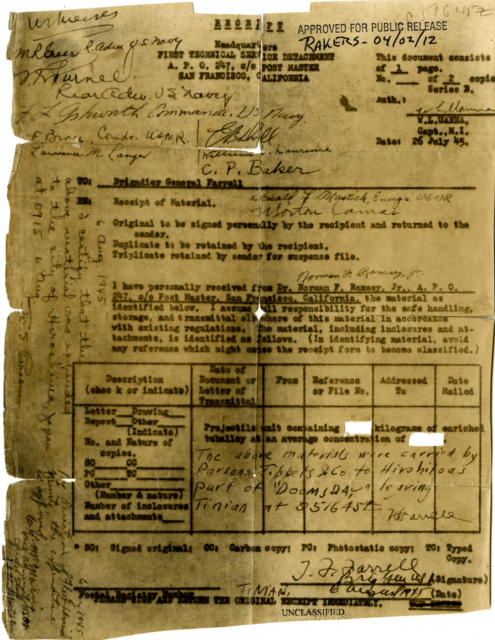

One of the official pieces of documentation for the delivery of Little Boy is a tattered receipt, which is perhaps one of the most unique receipts in history. The receipt was signed by Thomas Ferrell, the Deputy Director of the Manhattan Project, to confirm the successful handover of much of the Little Boy bomb’s components from Secretary of War’s staff Dr. Norman F. Ramsey.

Ramsey left the US with the USS Indianapolis, which made the journey across the Pacific in just ten days. Once the shipment arrived at Tinian, Ramsey signed over the bomb to Ferrell. After this, the pieces of the bomb were handed to the crews for preparation.

However, the receipt was not just proof of the delivery of the bomb but was also used to confirm the use of the bomb. Regardless of the destruction of the city, bureaucratic procedures required a piece of paper to officially confirm the use of the weapon.

To confirm its use, Fleet Admiral Nimitz’ Chief of Staff signed the receipt, writing: “By direction of Fleet Admiral Nimitz, the expenditure of this item is approved.”

Another signature on the receipt is from William S. Parsons, the weaponeer aboard the B-29 that dropped the Little Boy bomb, Enola Gay. He wrote: “I certify that the above materials was expended to the city of Hiroshima, Japan at 0915 6 Aug.”

More From Us: Lucky or Unlucky? The Man Who Lived Through Two Atomic Bombs

After it was signed, Ferrell kept hold of this historical document and had crew members on the Tinian sign it. For the rest of his life, Ferrell kept the receipt in his wallet and it is now the only example of its kind known to exist.

The receipt was donated to the Army Heritage and Education Center by Ferrell’s family, where it remains today.

Post a Comment

0 Comments