A German U-boat ended up at the bottom of Lake Michigan, here’s how it happened

Right now, resting at the bottom of Lake Michigan is a 185-ft German submarine. U-boats of the German Imperial Navy did close in on the United States during WWI, but they never entered the Great Lakes. So how is it then that this century-old piece of German hardware ended up at the bottom of the lake?

German U-boats after WWI

It was 1919, and WWI had ended in November of the previous year. After four vicious years of war, Europe was finally on the path to recovery. When the Armistice was signed, Germany was instructed to hand over its ships to the British. This was the start of a process that would lead to the dissection of Germany, military and financially. The Treaty of Versailles forced Germany to disarm and pay huge amounts in reparations for damage caused during the war.

Instead of handing their ships over, Germany broke the agreed terms of the Armistice and scuttled most of them. However, their U-boats managed to escape this fate and ended up in the hands of the British. Germany had been the technological leader of submarine warfare and design up until that point, so these U-boats were valuable pieces of equipment.

The British ended up with 176 U-boats in total and handed some of them to friendly nations to be studied. These submarines came with a stipulation though; that once their use was over, they were to be sunk in water deep enough to prevent any future salvage.

The US had little interest in accepting the U-boats, as they believed theirs were of better quality, and that soon submarines may be banned altogether (after WWI, the British were pushing hard for a total ban on submarines as weapons of war due to the destruction they caused).

But there were a few who saw the submarines as a means of making money. The cost of fighting WWI had left the US in enormous amounts of debt, which they were trying to pay off with bonds purchased by citizens.

It was thought that parading these enemy submarines around US ports and allowing the public to pay to see them would produce a nice boost in income to pay off their debt.

UC-97

UC-97 was one of six submarines brought over from Europe. She was a Type UC III, a class of late-war, relatively small minelaying U-boats. They were equipped with six minelaying tubes, three torpedo tubes, and a deck gun.

Over 100 Type UCIII U-boats were ordered, but the war cut production short with just 25 having been built. UC-97 was one of these. When she arrived in the US, the public was told about her record of seven ships sunk. However, UC-97 never actually saw combat, and her record was fabricated to make her more appealing to the public.

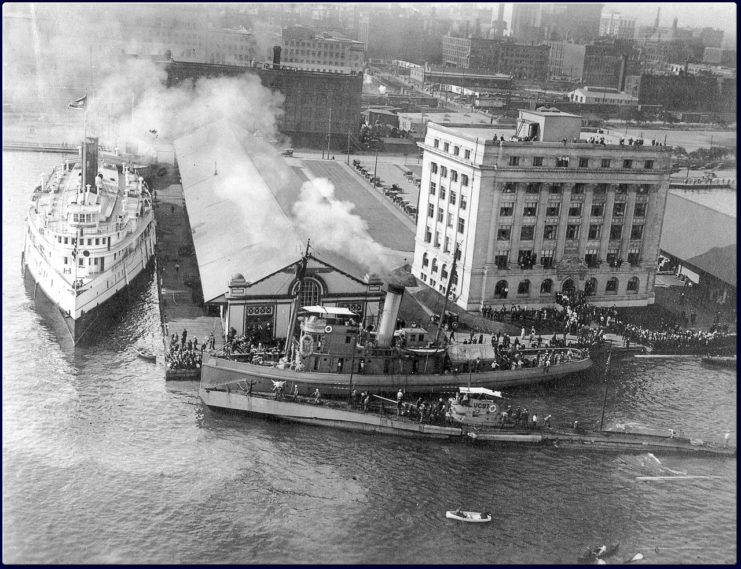

She spent much of this time in New York City, attracting thousands of visitors wherever it went. Once she had served her use making money, the submarine began more tours as part of a recruitment drive.

She toured the Great Lakes visiting places like Milwaukee and Chicago, and once again pulled in huge crowds, attracting so many people that ports often struggled to cope with them. After her tour was over, she was completely stripped of anything even remotely useful and moored up on the Chicago River.

The empty hull sat there until 1921. In June of that year, UC-97, lacking engines for propulsion, was towed out into Lake Michigan to fulfill the original agreement of sinking it once it was no longer useful.

UC-97 was to be used as a floating target for the gunboat USS Wilmette in a highly publicized event. She was hit by a number of 4-inch rounds before quickly sinking to the bottom of the lake, to be forgotten for much of the century.

Attempts to locate the vessel in the 1960s and 1970s were thwarted by a distinct lack of information about the submarine’s final moments. In 1992, UC-97 was finally discovered by A and T Recovery. Her location is not available to the public, but A and T Recovery have visited her multiple times since the discovery.

Post a Comment

0 Comments