The Battle of the Bismarck Sea Made it Mandatory For Japanese Soldiers To Learn How To Swim

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7 1941, the US and its allies in the Pacific were subjected to a series of Japanese victories, conquering territory after territory. It wasn’t until the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 and the Battle of Midway in June 1942 that the Japanese war machine was finally slowed down.

The Battle of Midway in particular was one of the most important battles of the entire war, costing the Japanese dearly in men, equipment, and vessels.

Battle of the Bismarck Sea

In late 1942, Japan realized they were at risk of losing control of the South West Pacific, particularly New Guinea. A series of Allied victories on New Guinea had weakened Japanese forces on the island, which were now in desperate need of supplies and reinforcements.

The Japanese decided to send around 7,000 troops and a huge amount of supplies from Rabaul to Lae, New Guinea, via a convoy. This idea was risky, as Allied airpower in the region could wreak havoc with the convoy should it be discovered. Nevertheless, the convoy left Rabaul and made its way to Lae.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, radio communications relating to the convoy had been intercepted by the Allies, who, with the help of codebreakers, knew both the convoy’s destination and arrival date. With the luxury of knowing the Japanese plans, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) began making preparations to stop the convoy reaching Lae.

US and Australian commanders planned to first establish the location of the convoy with reconnaissance aircraft. Once this was known, a series of intense attacks by land-based heavy, medium, and light bombers along with torpedo boats would attempt to completely destroy the convoy.

The commanders knew that for their complex plan to work, the coordinated attacks must be carried out with extremely precise timing. As inexperienced pilots would likely struggle with this, a series of mock-up battles were staged to practice the attack.

The crews were instructed to rendezvous at Cape Rodney. From there, they would fly 90 miles to Port Moresby, where they would begin a simulated attack on a ship in the harbor.

These practice runs helped crews improve their aim and timing for the real thing.

The Japanese convoy consisted of eight destroyers and eight troop transports and was covered by 100 escorting fighter aircraft. It left from Rabaul on February 28 1943 and planned to arrive in Lae on March 3.

The attack begins

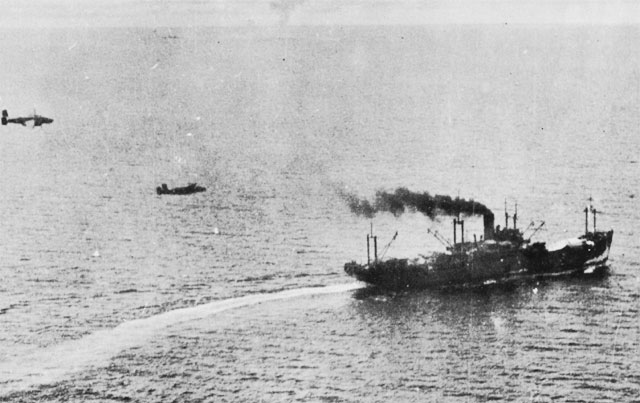

Japanese transport under aerial attack in the Bismarck Sea March 3, 1943. (Photo Credit: Public Domain)

To begin with, the convoy was blessed with poor weather that hid it from Allied reconnaissance aircraft. However, the convoy was spotted by a USAAF Liberator early on March 2, prompting General Whitehead, the battle’s US commander, to launch eight B-17s followed up by another twenty. A further eleven B-17s were launched towards the end of the day, claimed to have caused considerable damage to the convoy.

By the end of March 2, the convoy was approaching waters within the range of all Allied aircraft, at which point unreserved devastation would be unleashed. To make sure the attack began as soon as possible after daylight, a RAAF Catalina followed the convoy throughout the night, reporting its location.

Daylight broke on March 3 to clear skies, ideal conditions for an aerial attack.

That morning, fighter bases at Lae were attacked to limit Japanese defenses, while 90 Allied aircraft took off to attack the convoy.

RAAF and USAAF B-17 Flying Fortresses, P-38 Lightning, B-25 Mitchells, Beaufighters, and A-20 Bostons repeatedly attacked the convoy over the course of the day.

The heavily armed Beaufighters strafed the ships at an extremely low level in an attempt to destroy their anti-aircraft capabilities and kill their captains and officers. The B-17s conducted medium-level bombing against the ships while the B-25s and A-20s attacked at extremely low altitudes. At the same time, the P-38 Lightnings engaged Japanese escort fighters above the chaotic battle.

The convoy was wiped out

The battle ended with a devastating Japanese defeat. All eight transports and four of the eight destroyers were sunk. The remaining destroyers transported 2,700 troops back to Rabaul, but 1,000 Japanese men were left afloat in the ocean. It was feared that any Japanese survivors that made their way to land would resume fighting the Allies, so for the next few days, Allied boats and aircraft combed the ocean, firing at the stranded survivors bobbing in the water or clinging to wreckage.

More From Us: Modern Technology Reveals Secret of the Sinking of the Bismarck

Overall, the Japanese lost eight transports, four destroyers, twenty fighters, and nearly 3,000 men. In return, the Allies lost just two bombers, four fighters, and 13 men.

After the defeat at the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, Japan issued an order to ensure every soldier was able to swim.

Post a Comment

0 Comments