The Battle of Los Angeles: The Enemy Attack That Never Happened

The United States entered WWII after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The bombing put the entire nation on high alert, and tensions ran high. It’s speculated that this paranoia is the reason behind one of the most unusual incidents to occur on U.S. soil during the conflict: the Battle of Los Angeles.

Paranoia after Pearl Harbor

The months following the attack on Pearl Harbor saw the population fearing another attack or invasion. This fear was worsened by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, who warned Americans should prepare for “occasional blows” from the enemy. In response, people began mobilizing. Anti-aircraft guns were installed across the country, bunkers built and air raid precautions drilled into the civilian population.

The paranoia hit its peak on the west coast after attacks on American merchant ships by the Japanese between December 1941 and February 1942. Everyone was on edge, so much so that inexperienced radar men kept mistaking fishing boats and marine life for enemy warships and submarines.

Rumor spread regarding the Japanese Army’s proximity to the mainland. It was thought a Japanese aircraft carrier was sailing off the coast of San Francisco, which led the city of Oakland to close its schools and issue a city-wide blackout. These rumors were taken so seriously that 500 U.S. Army troops were stationed at Walt Disney Studios, in order to protect it and nearby industry from attack.

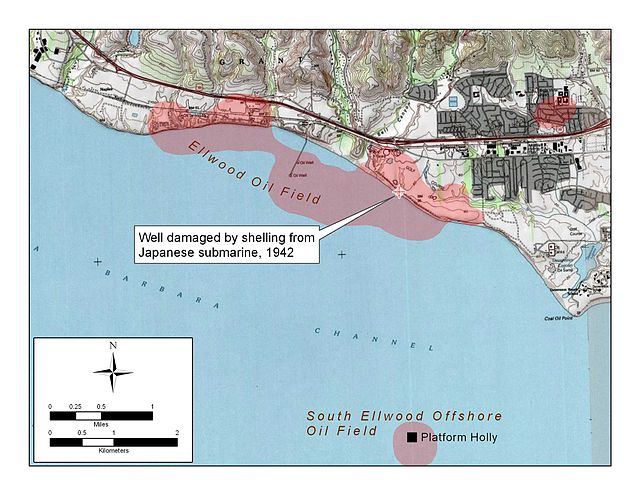

Bombardment of Ellwood

On the evening of February 23, 1942, the west coast saw its worst fears realized when Japanese submarine I-17 surfaced near Santa Barbara and attacked the Ellwood Oil Field. It hurled approximately two dozen artillery shells, and the attack marked the first and only time the mainland was bombed during WWII.

Overall, damage caused by the attack was minimal and no one was injured. However, the damage was done to the psyche of those living on the west coast, who began to worry the Japanese could invade at any moment.

The Battle of Los Angeles

Following the attack on Ellwood, the Office of Naval Intelligence, on February 24, 1942, issued a warning, stating California could expect an attack within the next 10 hours. That evening, flares and blinking lights were reported and an alert was raised. It was lifted a few hours later.

Around 2:25 a.m., military radar picked up what appeared to be enemy activity approximately 120 miles west of Los Angeles. Air raid sirens sounded and a blackout was ordered. Troops took their posts at the anti-aircraft guns and used their searchlights to sweep the sky.

At approximately 3:16 a.m., the 37th Coast Artillery Brigade began firing 12.8-pound anti-aircraft shells and .50-caliber machine guns into the air. In total, over 1,400 shells were fired. Before long, other coastal defense weapons joined, except for the IV Fighter Command. While on alert, its pilots remained grounded.

The artillery fire continued sporadically over the next few hours, until the all-clear was signaled at 7:21 a.m. Throughout the night, unconfirmed reports came in of sightings of Japanese aircraft and paratroopers. There was even a report that a Japanese airplane crashed into the streets of Hollywood.

Direct aftermath of the Battle of Los Angeles

When crews searched the debris, they found no planes or personnel. In fact, it appeared there hadn’t been an enemy attack at all. The only damage was the result of friendly fire, as anti-aircraft shrapnel had damaged buildings. There were five casualties, all civilians. Two had died from heart attacks, while three perished in car accidents.

Based on the evidence, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox held a press conference, where he stated the raid had been a false alarm due to growing anxiety and nerves over the war. House Representative Leland M. Ford called for a Congressional investigation into the incident, as he felt that and other explanations didn’t fully explain the incident.

Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army General George C. Marshall blamed the firefight on enemy agents flying commercial airplanes over the mainland in an attempt to instill mass hysteria. However, people were skeptical of this explanation and he later backpedaled on his statement.

After the war, the Japanese government released its own statement, claiming it never flew any airplanes over the U.S. during the conflict.

Theories

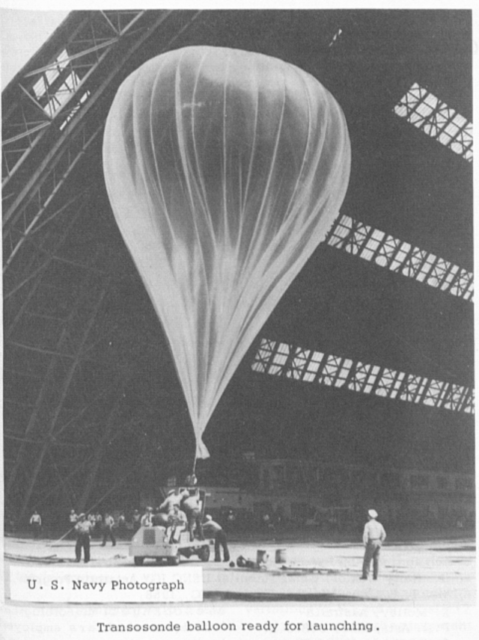

Most believe the airborne item initially believed to be an enemy aircraft was actually a weather balloon. In 1949, the U.S. Coast Artillery Association noted a balloon had been set aloft at approximately 1:00 a.m. the morning of February 25, 1942. It stated the device “started all the shooting” and concluded that “once the firing started, imagination created all kinds of targets in the sky and everyone joined in.”

Additionally, the U.S. Office of Air Force History concluded in 1983 that the event was a case of “war nerves” and the weather balloon, which had been released to determine wind conditions, had become lost. Its lights and color may have triggered the alerts and spurred the anti-aircraft guns into action.

Some believe an enemy attack did happen and was covered up. It was speculated a secret base had been built in northern Mexico and that the Japanese had stationed submarines offshore with airplanes within them. Others believed it a tactic staged in order to give defense industries an excuse to move inland.

Conspiracy theorists lean toward the belief the object seen is evidence of extraterrestrials. This was exacerbated by a photo published in the Los Angeles Times on February 26, 1942, featuring searchlights trained on an ovular object in the sky. Said object was never recovered, nor seen again.

More from us: Did The Trojan War Really Happen? Here’s What We Know

However, many don’t believe the photo is proof of an extraterrestrial visit, given it was retouched before publishing. Retouching photos was common practice in order to improve the contrast of black and white images, meaning the appearance of an UFO is likely the result of that process.

Post a Comment

0 Comments