Iva Toguri D’Aquino: The ‘Tokyo Rose’ Who Tried To Help The Allies

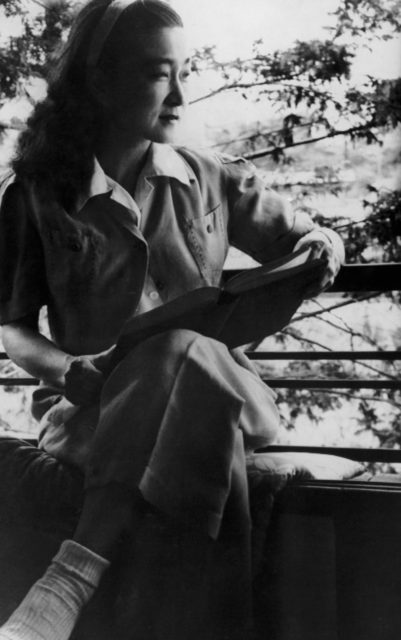

Many Americans found themselves stranded abroad during WWII. One such individual was a woman named Iva D’Aquino (née Toguri). She spent part of the war stranded in Japan, where she worked in radio and attempted to turn the Japanese propaganda machine on its head.

Iva’s voyage to Japan

Iva Toguri was born on July 4, 1916, to Japanese immigrant parents. The family resided in Los Angeles, California. Growing up, Iva’s father discouraged his children from engaging in Japanese activities, wanting the family to appear as American as possible. This meant Iva wasn’t allowed to speak Japanese or attend cultural events, and her meals were often a blend of Asian and Western cuisine.

In 1941, Iva’s parents sent her to Japan to care for her ailing aunt, who was bedridden with high blood pressure and diabetes. Travel to Japan was fraught with difficulties by that time, as it and the U.S. weren’t on the best terms. As such, Japanese-Americans fell under suspicion whenever they requested travel documents.

Iva traveled to Japan with a Certificate of Identification, as she didn’t possess a passport. She had a hard time adjusting to life there, as she was unable to speak the language and found people to be “discourteous.”

The language barrier was her biggest hurdle, as she couldn’t read local newspapers and learn that tensions between Japan and America were reaching a boiling point.

Japan attacks Pearl Harbor and war is declared

It wasn’t until November 1941 that Iva decided to return to Los Angeles. However, an issue with her paperwork meant she would miss her California-bound boat scheduled for December 2, 1941. Less than a week later, Japan attacked Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor and the U.S. declared war.

Iva was immediately approached by the Japanese government with a request to renounce her American citizenship. When she declined to do so, she was barred from obtaining a war ration card. She was deemed an “enemy alien” and watched closely. When she requested to be interned with other “enemy aliens,” she was denied due to her gender and Japanese ancestry.

Unable to return home, Iva remained at her aunt’s residence. She soon found herself forced out by neighbors who believed her to be an “American Spy.” In need of somewhere to live, Iva relocated to a boardinghouse in Tokyo.

Iva’s beginnings in Japanese radio

Iva obtained a part-time transcribing job with the country’s national news agency, Dōmei Tsūshinsha. It was there she learned of her family’s relocation to an internment camp in Arizona, a fate many Japanese-Americans living on the west coast faced. She also met her future husband, Portuguese-Japanese pacifist Felipe D’Aquino, while at the station. An act of generosity on his part would lead her to obtain another job, this time at Radio Tokyo.

While with Radio Tokyo (formally known as Nippon Hoso Kyokai), Iva worked as an English-language typist. It was during this time that she began smuggling food to inmates at a local P.O.W. camp, resulting in a meeting with Australian Captain Charles Cousens and U.S. Army Captain Wallace Ince.

Cousens and Ince, along with Philippine Lieutenant Normando “Norman” Reyes, were approached by Japanese officials to host a propaganda radio show. Titled Zero Hour, it aimed to lower the morale of troops stationed in the Pacific by reporting on disasters back in the U.S.

Initially written by the Japanese, complaints over poor English grammar and syntax eventually allowed the three soldiers to gain full control over the content. Due to the language barrier, they were able to fill their broadcasts with sarcasm and double entendres aimed toward the Japanese, without retribution.

Iva Toguri becomes “Orphan Ann”

The group soon approached Iva and requested she join them. She agreed, but under one condition: that she not be made to say anything anti-American on air. Soon, she was broadcasting under the pseudonym “Orphan Ann” — a play on the Little Orphan Annie comics and the phrase used by Australian soldiers to describe those cut off from allies: “Orphans of the Pacific.”

During Zero Hour‘s year and a half run, Iva performed various comedy sketches and introduced music, but never participated in newscasts. She called listeners “honorable boneheads” in mock contempt and refused to travel down the typical propagandist route.

Her on-air time eventually dropped to two to three minutes per broadcast, and her voice became known across the Pacific. While her identity and that of other female propagandists remained largely unknown, troops dubbed them the “Tokyo Rose.” This name became legendary and caused a lot of legal hardship for Iva.

Accusations of treason

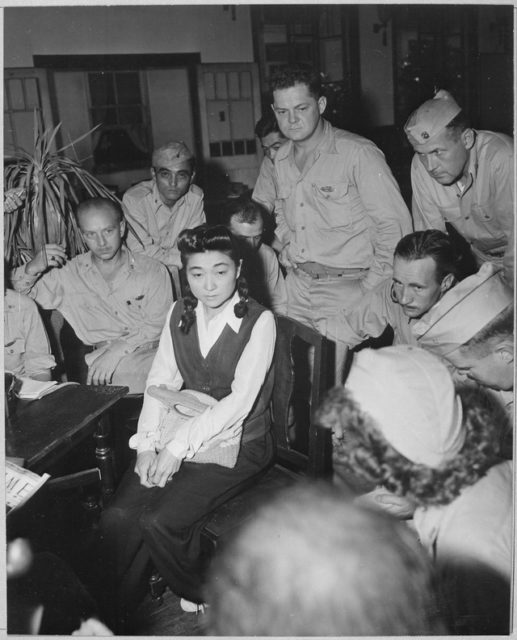

At the end of the war, reporters with Cosmopolitan Magazine and the International News Service put out a reward for $2,000 for an interview with the “Tokyo Rose.”

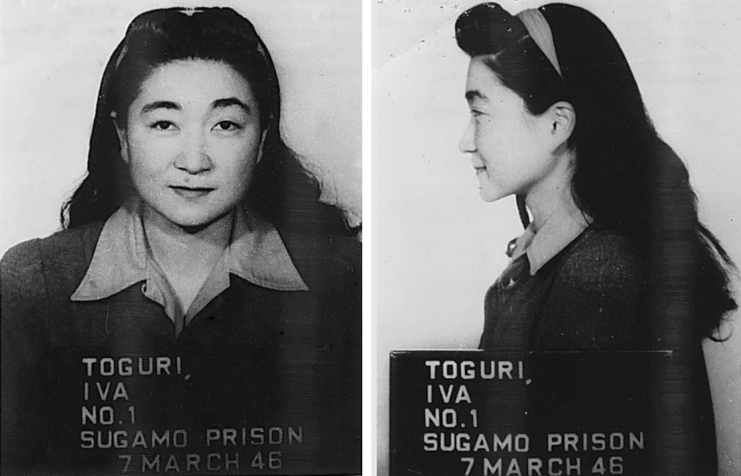

Despite not identifying as such, Iva took the offer, as she was in need of money to fund her voyage back to America. However, when she arrived in Yokohama on September 5, 1945, she was taken into custody by the U.S. Army. Her offense was treason for aiding the enemy with her radio broadcasts.

Iva was released from custody a year later, after the Army and other counterintelligence agencies found no evidence of treason during her time on Japanese radio. However, anti-Japanese sentiment was rampant in post-war America, meaning she was in for a rough ride upon returning home.

Arrested for the second time on September 25, 1948, Ida faced eight charges of treason. Her trial hinged on two key pieces of evidence. The first was a group of Japanese witnesses who claimed she’d spoken badly about the U.S. on-air.

The second was a supposed line — “Orphans of the Pacific, you are really orphans now. How will you get home now that your ships are sunk?” — that she’s said to have uttered in October 1944.

Despite the quote not appearing in the show’s transcripts, it proved to be the deciding factor in the case. Iva was sentenced to 10 years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Her U.S. citizenship was also revoked.

She spent six years and two months at the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, before being granted parole.

Presidential pardon

Iva moved to Chicago to work for her father’s business upon her release, but she couldn’t escape the trouble of being known as the “Tokyo Rose.” The federal government issued a deportation order against her, and she was consistently denied a presidential pardon for her conviction.

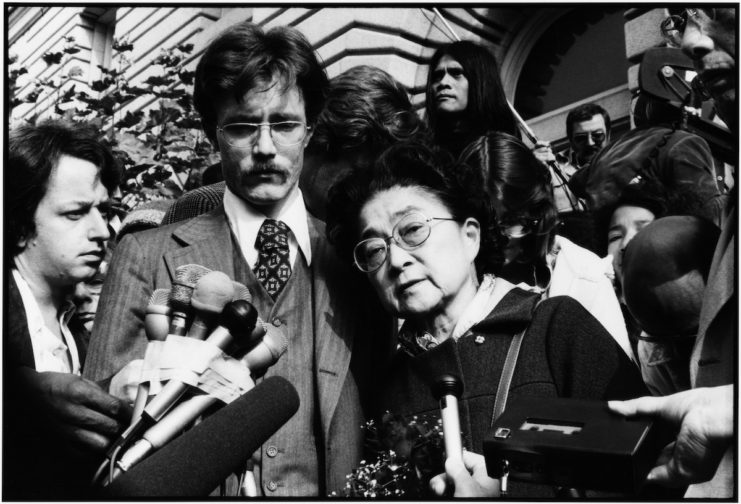

Things turned around in 1976 after two witnesses from the trial claimed they’d been threatened into testifying against Iva. This led the jury foreman to admit the presiding judge had pressured the jury to come back with a guilty verdict.

Journalists and government agencies investigated Iva’s conviction and found numerous other issues, which led advocacy groups to petition again for a presidential pardon.

More from us: The Bomber Mafia: Success, But At What Cost?

On the last full day of his presidency in 1977, President Gerald Ford granted Iva a presidential pardon, nullifying her conviction. The pardon also restored her U.S. citizenship.

After being pardoned, Iva continued to live in Chicago. She unfortunately had to divorce her husband in 1980, after he was denied entry into the U.S., but she lived a relatively private life and died of natural causes in September 2006.

Post a Comment

0 Comments